Ultrasound Journal 39 - Ultrasonic Diagnosis of Müllerian Duct Anomalies

OBG academic CAS - Asia Pacific Kathleen M. Cruz 2025-12-04

Case Introduction

Müllerian duct anomalies (MDAs) are congenital malformations of the uterus, cervix, and vagina, result from defective development, fusion, or resorption of the Müllerian ducts during embryogenesis.

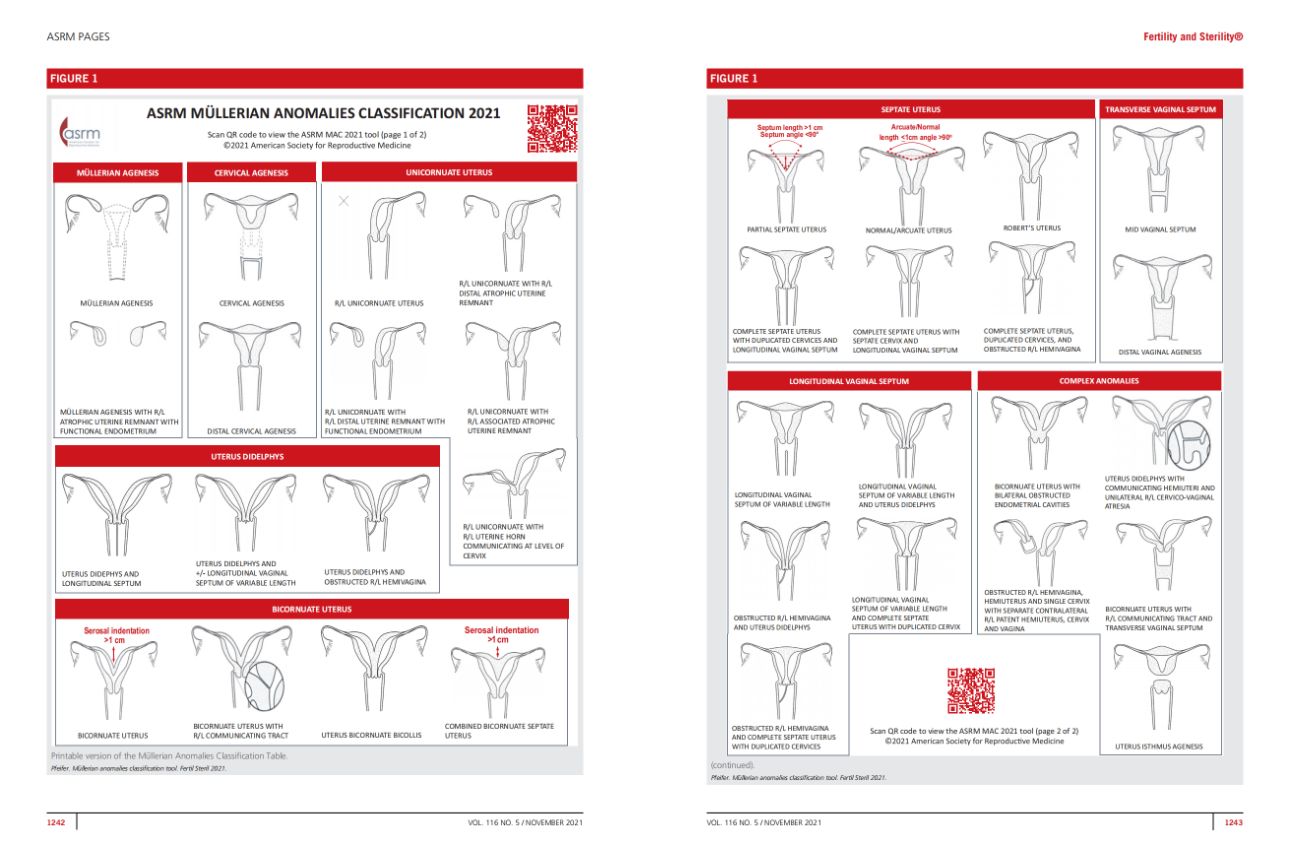

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s 2021 Müllerian Anomalies Classification (MAC 2021) introduces a simplified, clinically focused approach to categorizing anomalies by uterine, cervical, and vaginal origin, while acknowledging overlap between categories [1].

These anomalies occur in approximately 2–4% of women and are often associated with infertility, recurrent miscarriage, and adverse obstetric outcomes [2,3]. Early identification is therefore crucial for guiding reproductive management and improving outcomes.

Ultrasonography has become the first-line imaging modality for evaluating MDAs due to its accessibility, safety, and high diagnostic accuracy [4].

The introduction of high-resolution transvaginal and three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound has significantly improved the assessment of uterine contour and endometrial cavity morphology. Compared with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound provides real-time, cost-effective, and dynamic evaluation, making it indispensable in routine gynecologic practice [5].

This report presents a clinical case demonstrating the role of ultrasonography, particularly 3D and Smart ERA analysis, in diagnosing congenital uterine malformation.

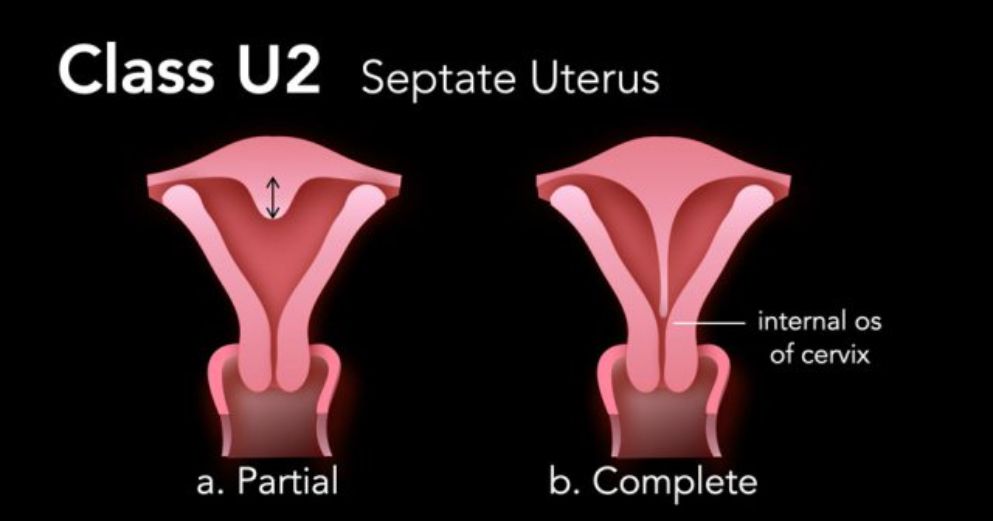

Clinical Case – Septate Cervix and Uterus

A 30-year-old female presented for a pelvic ultrasound as part of her routine preconception evaluation, as she was planning to conceive. The objective of the scan was to assess her reproductive anatomy—including the uterus, endometrium, adnexa and vagina—to ensure there were no abnormalities that could affect fertility or future pregnancy outcomes.

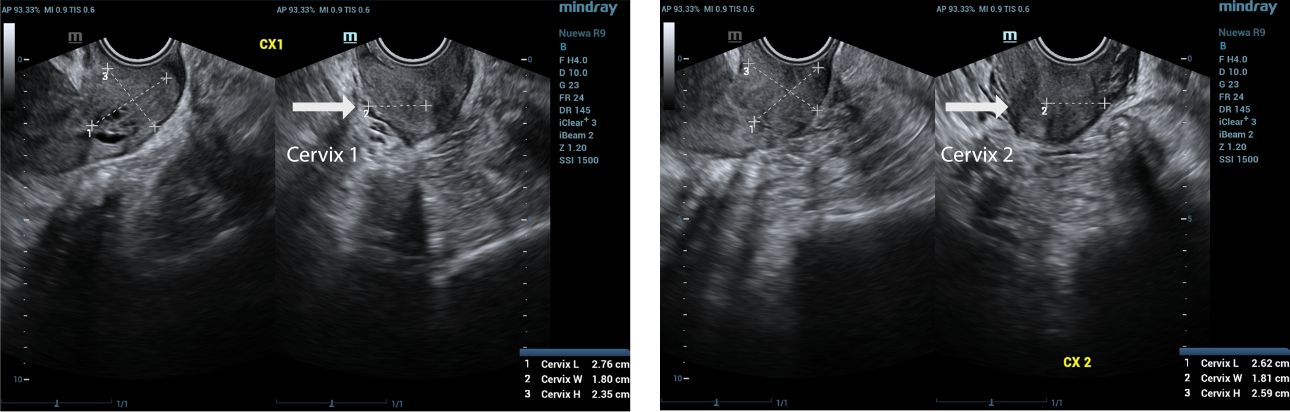

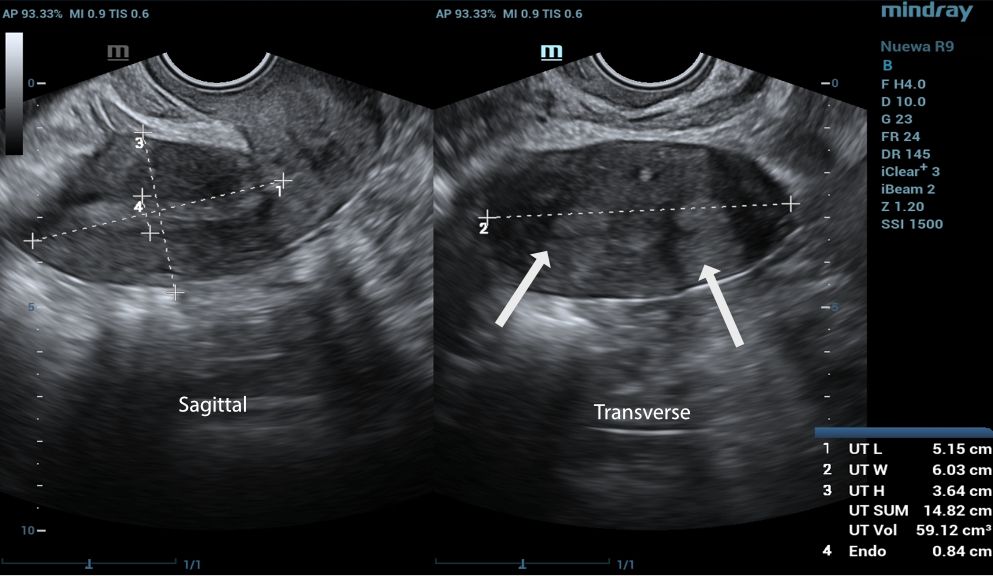

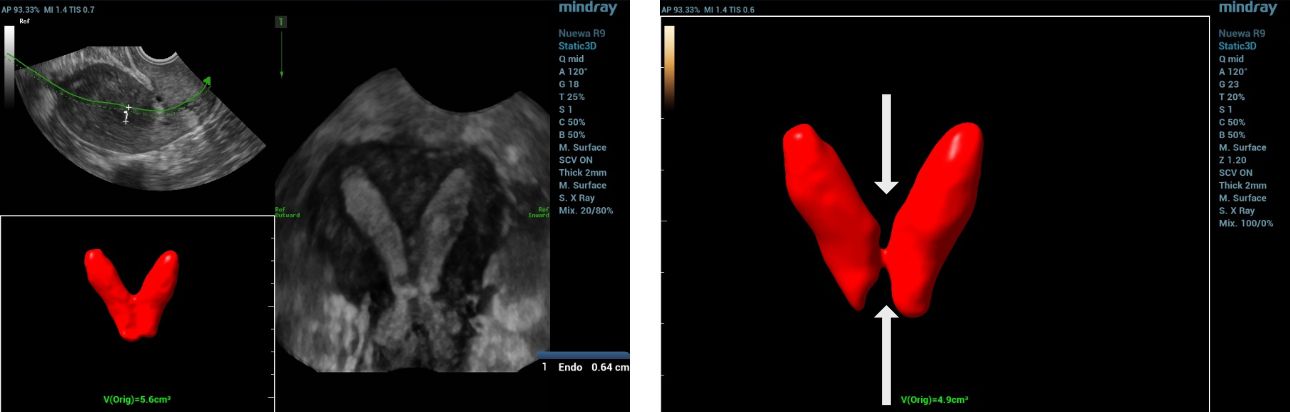

A transvaginal two-dimensional (2D) gynecologic ultrasound was initially performed, capturing both transverse and sagittal views of the uterus.

During the ultrasound examination, we observed a normal vagina and two cervixes. On the transverse view, two distinct endometrial echoes were visualized, raising suspicion for a possible congenital uterine anomaly such as a septate or bicornuate uterus.

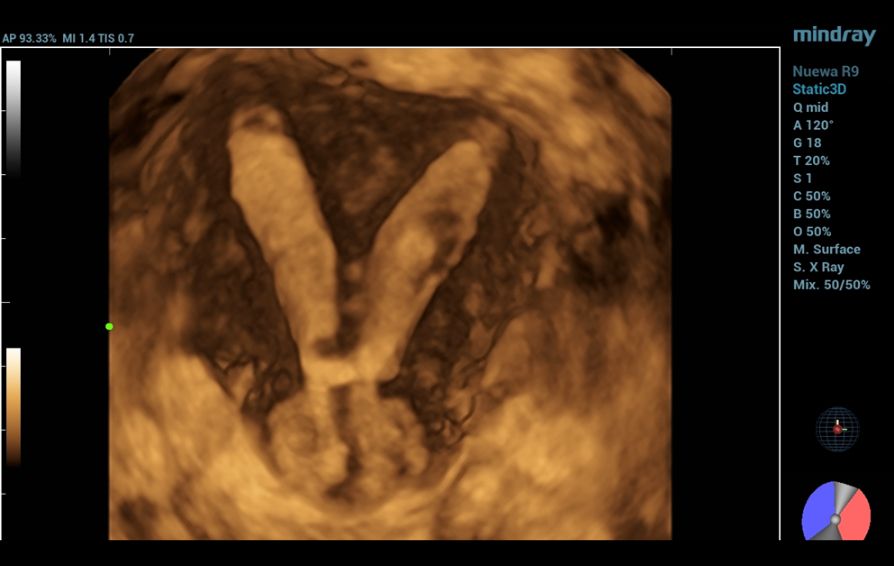

To further assess the anatomy, a 3D ultrasound was conducted, which provided the true coronal view of the uterus. This enabled better visualization of the uterine cavity and external contour, allowing for more accurate classification.

Based on the 3D ultrasound findings, the impression was complete septate uterus with septate cervix.

Septate uterus is a common benign uterine congenital anomaly with an estimated prevalence of ~2 % in the general population, ~3 % in infertile women and >5 % in patients with recurrent pregnancy losses.

Furthermore, the application of Smart ERA (Endometrial Receptivity Analysis) enhanced the diagnostic evaluation by providing automated, high-resolution analysis that clearly delineated the septate uterus and septate cervix, thereby supporting the 3D ultrasound findings.

Discussion

Congenital uterine anomalies arise from abnormal Müllerian duct development and are often linked to infertility, recurrent pregnancy loss, and adverse obstetric outcomes [6]. Differentiating between anomalies, especially septate and bicornuate uterus, is crucial for proper management.

Three-dimensional ultrasonography is now the gold standard for evaluating uterine morphology, offering clear visualization of both the cavity and external contour [7]. In this case, 3D ultrasound accurately identified a complete septate uterus with septate cervix, a diagnosis that could be easily missed with 2D imaging.The addition of Smart ERA provided automated analysis and clearer delineation of the septal structure, enhancing diagnostic precision and reducing operator dependency. Early and accurate detection supports timely reproductive counseling and appropriate management [8].

For evaluating vaginal malformations (e.g., Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich Syndrome), the transrectal biplane high-frequency ultrasound probe is valuable. It avoids limits of transabdominal/transvaginal methods, offers clear vaginal visualization via high resolution, and improves accuracy with sonovaginography. It aids confirming malformation type/severity, guides treatment, and complements 3D uterine ultrasound for holistic assessment, supporting better outcomes [9].

Conclusion

Ultrasonography, particularly three-dimensional (3D) imaging, remains the cornerstone in the evaluation of congenital uterine and vaginal anomalies. It provides accurate, non-invasive, and real-time assessment of uterine morphology, enabling differentiation between anomaly types and guiding clinical management.

This case highlights the crucial role of advanced ultrasound techniques—particularly the integration of Smart ERA—in enhancing diagnostic precision.

The automated analysis clearly delineated the septate uterus with septate cervix, reinforcing the 3D findings and supporting accurate classification. Early diagnosis through such technologies is vital in optimizing reproductive outcomes and informing appropriate patient counseling.

References:

[1] Pfeifer SM, Attaran M, Goldstein J, Lindheim SR, Petrozza JC, Rackow BW, Siegelman E, Troiano R, Winter T, Zuckerman A, Ramaiah SD. ASRM müllerian anomalies classification 2021. Fertil Steril. 2021;116(5):1238-1252.

[2] Grimbizis GF, Gordts S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, et al. The ESHRE–ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(8):2032-2044.

[3] Chan YY, Jayaprakasan K, Zamora J, et al. The prevalence of congenital uterine anomalies in unselected and high-risk populations: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(6):761-771.

[4] Salim R, Woelfer B, Backos M, Regan L, Jurkovic D. Reproducibility of three-dimensional ultrasound diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21(6):578-582.

[5] Troiano RN, McCarthy SM. Müllerian duct anomalies: imaging and clinical issues. Radiology. 2004;233(1):19-34.

[6] Ludwin A, Ludwin I. Comparison of the ESHRE–ESGE and ASRM classifications of Müllerian duct anomalies in everyday practice. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(3):569-580.

[7] Bermejo C, Martínez Ten P, Cantarero R, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies and concordance with magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(5):593-601.

[8] Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Gong J, et al. Clinical utility of three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of uterine anomalies and its impact on reproductive outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:364.

[9] Chen X, Wang L, Luo H. The Value of Transrectal Biplane High-Frequency Ultrasound Combined With Sonovaginography in the Classification of Herlyn–Werner–Wunderlich Syndrome. J Clin Ultrasound. 2025; :960-962.