Special thanks for Gil Pugliese, Savino; Dolgonos, Camila; Simes, Luciana; Taborda, Cecilia; Rizzotti, Alina; Ducart, Florencia; Tapia, Natalia; Juaneda, Ignacio; Peirone, Alejandro from Hospital Privado Universitario de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina, Vega, Betina; De Breuil, Marcela; Mazer, Alicia from Nueva Maternidad Provincial Brigadier General Juan Bautista Bustos, Córdoba, Argentina and Goizueta, Manuela from Hospital Materno Neonatal, Posadas, Misiones, Argentina.

Introduction

Fetal intrapericardial teratomas are rare. Among fetal primary cardiac tumors, rhabdomyomas are the most common, followed by teratomas, fibromas, hemangiomas, and myxomas. Teratomas are seen as single well-demarcated masses with a cystic component. They are usually located in the proximities of the outflow tracts and typically present with severe pericardial effusion.

Although intrapericardial teratomas are benign, massive pericardial effusion can be life-threatening for the fetus due to cardiac tamponade. Severe pericardial effusion, together with the mass effect caused by the tumor, can impair systemic venous return leading to hydrops in approximately 70% of the cases. Similarly, esophageal compression can impair swallowing and cause polyhydramnios in approximately 25% of the cases, increasing the risk of preterm premature rupture of membranes. Therefore, management is driven by the risk of cardiac tamponade and the development of hydrops and/or polyhydramnios [1].

Ultrasound-guided serial pericardiocentesis or pericardio-amniotic shunting can drain the pericardial effusion and decrease intrathoracic pressure. Alternatively, ultrasound-guided intratumoral laser has been reported to be effective in delaying tumoral growth and recurrence of pericardial effusion [2].

Early antenatal diagnosis and timely fetal treatment are crucial in improving survival as postnatal surgical resection is usually curative [3].

Case Presentation

A 41-year-old woman, gravida 4 para 3, was diagnosed with a fetal cardiac tumor presenting with severe pericardial effusion at 19 weeks + 3 days of gestation. No signs of hydrops or polyhydramnios were seen. Fetal karyotype was normal. The mother was referred to our institution at 22 weeks of gestation, traveling 1150 kilometers, for further management.

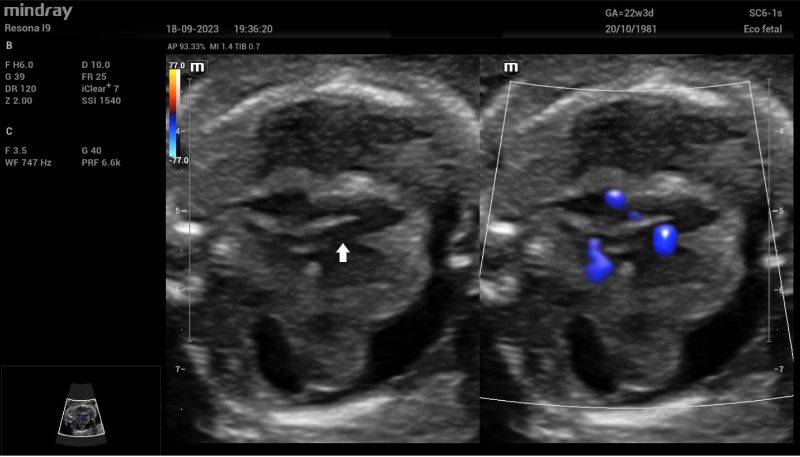

Upon admission, fetal echocardiography revealed a well-defined intrapericardial bilobed mass, measuring 20 mm x 16 mm x 10 mm, located in the free wall of the left atrium and left ventricle at the level of the mitral valve and presenting with severe pericardial effusion (Fig. 1).

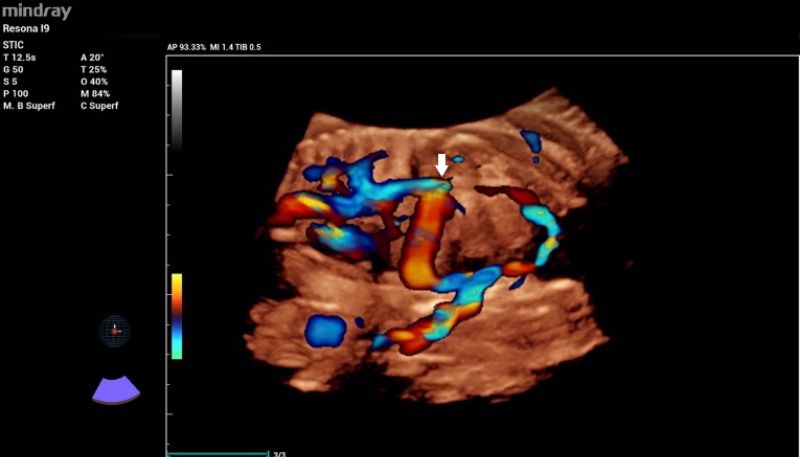

Additionally, a wide muscular ventricular septal defect (VSD) (Fig 2). and agenesis of the ductus venosus with extrahepatic drainage to the inferior vena cava (Fig 3). were diagnosed.

Considering the difficulties of the patient in accessing urgent fetal treatment due to the long distance to our hospital, at 22 weeks and 3 days, under maternal sedation and fetal anesthesia, ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis was performed to prevent cardiac tamponade and fetal hydrops (Fig 4). Fifteen milliliters of bloodstained pericardial fluid was obtained and sent for pathological examination. The cytological sediment showed abundant small, mature-looking lymphocytes, with no malignant epithelial or mesenchymal cells. After 24 hours, the patient was discharged and sent back to her local hospital for monitoring.

The pericardial effusion reappeared rapidly over the next two weeks. Therefore, at 24 + 2 weeks gestation, under maternal sedation and fetal anesthesia, a Harrison fetal stent catheter (double pig tail) was placed through the fetal right hemithorax (Fig. 5). Additionally, 11 ml of pericardial fluid were drained via pericardiocentesis. The shunt remained in place, the pericardial effusion didn’t reaccumulate, and the tumor decreased in size throughout the pregnancy, being barely visible at the end of the third trimester.

At 37 weeks, the patient reported pre-labor rupture of membranes, prompting a cesarean section. The 2650 g male newborn cried immediately; after 30 seconds, the cord was clamped. Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes were 7 and 8, respectively. Upon examination, the baby presented with cyanosis and mild subcostal retraction, necessitating non-invasive ventilation with nasal continuous positive airway pressure, which improved oxygen saturation and breathing patterns.

The baby was hemodynamically stable, so the cardiovascular surgery team removed the pericardio-amniotic shunt (Fig. 6). Umbilical catheterization was performed, and the baby was fed via an orogastric tube. A transthoracic echocardiography revealed a 12 mm x 8 mm VSD, a persistent ductus arteriosus of 2 mm with no pulmonary stenosis, and a normal aortic arch. No cardiac masses were found.

At 47 days of life, the baby presented high-output heart failure, requiring surgical correction of the VSD. The tumor was not visible at the time of cardiac surgery, but multiple pericardial samples in the tumoral area were taken. Histopathological examination reported mature teratoma in one of these specimens.

Discussion

Teratomas are primary benign germ cell tumors containing derivatives of endodermal, mesodermal, and neuroectodermal germinal layers. They commonly affect the testes, ovaries, and the sacrococcygeal area. Occasionally teratomas can present in the pericardium. Fetal intrapericardial teratomas are rare. Prenatal diagnosis is based on the ultrasonographic finding of a multi-cystic cardiac mass typically associated with severe pericardial effusion, usually presenting at the end of the second trimester, hence not visible at the time of the routine second-trimester scan.

Fetal therapy aims to release mediastinal pressure to avoid cardiac tamponade, fetal hydrops, pulmonary hypoplasia, and polyhydramnios.

The management of a prenatal intrapericardial teratoma depends on the gestational age at diagnosis and the presence of fetal hydrops and/or polyhydramnios. If the teratoma is detected late in pregnancy, delivery by caesarean section is recommended to avoid chest compression during vaginal delivery. Additionally, elective caesarean section allows timely multidisciplinary management of the newborn.

When the teratoma complicates previable or preterm pregnancies, fetal therapy can be offered in cases presenting with hydrops or polyhydramnios. Ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis is the most widespread method as it is minimally invasive and technically simple. Still, reaccumulation of pericardial fluid requires multiple procedures, especially when diagnosed early in gestation. Alternatively, a pericardio-amniotic shunt can be placed to avoid repeated invasive procedures, although it might be technically more challenging. Additionally, the size of the trocar used for shunting is bigger than the needle used for pericardiocentesis and therefore, the risk of PPROM might be slightly higher [4].

Intratumoral ultrasound-guided laser has been reported to cause tumoral necrosis, aiding in stopping tumoral growth, but evidence is scarce.

Teaching point

- Intrapericardial teratomas are single, multi-cystic, well-defined masses, typically presenting with severe pericardial effusion. They are usually not seen during the second trimester anomaly scan as they grow later in gestation.

- The tumor was easily detected using bidimensional ultrasonography with our Mindray scanning machine.

- 3D volumes were stored to obtain the expert’s opinion later on when discussing the case in a multidisciplinary meeting.

- Cardiac teratomas are usually isolated, but a detailed anatomical scan and a fetal echocardiogram are needed to rule out additional abnormalities.

- Dual 2D and Color Doppler imaging available in our Mindray scanning machine helped in diagnosing the coexisting ventricular septal defect.

- In this particular case, 3D color Doppler reconstruction allowed detailed evaluation of the venous system and was crucial for understanding the ductus venosus abnormal drainage.

- Hydrops affects around 70% of the cases with intrapericardial teratoma, prompting active management.

- Polyhydramnios due to esophageal compression can increase the risk of premature preterm rupture of membranes.

- Serial pericardiocentesis, pericardial-amniotic shunting and/or intratumoral laser can be performed to treat this condition prenatally.

- The high resolution of our Mindray machine was crucial for performing pericardiocentesis and pericardial-amniotic shunting in an accurate and safe way.

References:

[1]. Gil-Pugliese S, Taborda GC, Juaneda I, Tapia N, Rizzotti A, Ducart F, Vega B, Simes L, Ricart D, Estupiñan W, Molina-Giraldo S, Peirone A. Manejo perinatal del embarazo gemelar discordante para teratoma intrapericárdico. Comunicación de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Rev peru ginecol obstet. 2024;70(1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.31403/rpgo.v70i2600

[2]. Molina FS, Romero B, Acosta I, Arévalo, E. Ablación láser percutánea de un teratoma cardiaco fetal y revisión de la literatura. Diagnóstico Prenatal. 2012;23(4):154-9.

[3]. Nassr AA, Shazly SA, Morris SA, Ayres N, Espinoza J, Erfani H, Olutoye OA, Sexson SK, Olutoye OO, Fraser CD Jr, Belfort MA, Shamshirsaz AA. Prenatal management of fetal intrapericardial teratoma: a systematic review. Prenat Diagn. 2017 Sep;37(9):849-63. doi: 10.1002/pd.5113

[4]. Tomek V, Vlk R, Tláskal T, Skovránek J. Successful pericardio-amniotic shunting for fetal intrapericardial teratoma. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010 Nov;31(8):1236-8. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9774-x