While outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases like chikungunya periodically emerge in regions from Asia to the Americas, a more familiar and relentless threat continues to demand global attention: dengue fever. Transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, dengue is expanding its reach, fueled by urbanization, climate change, and uneven public health infrastructure. This expansion is turning rural areas into new frontlines in the battle against outbreaks.

A Growing Global Health Crisis

In India alone, dengue affects over a million people each year, posing not only a threat to individual health but also placing a socioeconomic burden of approximately $1.1 billion annually on the healthcare system. How to address this challenge with more accessible and efficient medical technology has become a critical issue in global public health.

Data from the World Health Organization shows that in the past two decades, the number of dengue fever cases worldwide has increased tenfold, with particularly severe outbreaks in Southeast Asian countries such as India. Dengue fever has become one of India’s major health crises, especially during the monsoon season.

The Clinical Dilemma:

Uncertainty in Diagnosis and Care

“Dengue is like a storm that lasts anywhere from seven days to two weeks. While it’s a relatively short period, dramatic changes can occur both in the patient’s body and in lab results,” said Dr. Subhadip Pal, Internal Medicine Specialist at HP Ghosh Hospital in Kolkata. “That’s why we maintain close communication with our paramedic, pathology, and biochemistry teams throughout.”

However, in primary healthcare facilities, challenges such as insufficient testing equipment and a shortage of specialized personnel make early detection and timely intervention difficult. This situation not only raises the risk of delayed treatment but also increases the likelihood of unnecessary blood transfusions, creating a potential hazard for cross-infection.

Dr. Sheela Devi

HOD Pathology

JSS Hospital, Mysuru

Mindray's Cellular Analysis Line not only help in assessing recovery trends but also offers an integrated provision for preparing & staining peripheral blood smears. This helps in validating the results thereby ensuring accurate and comprehensive evaluation of dengue patients.

The Science of Survival:

How Dengue Attacks and How Medicine Responds

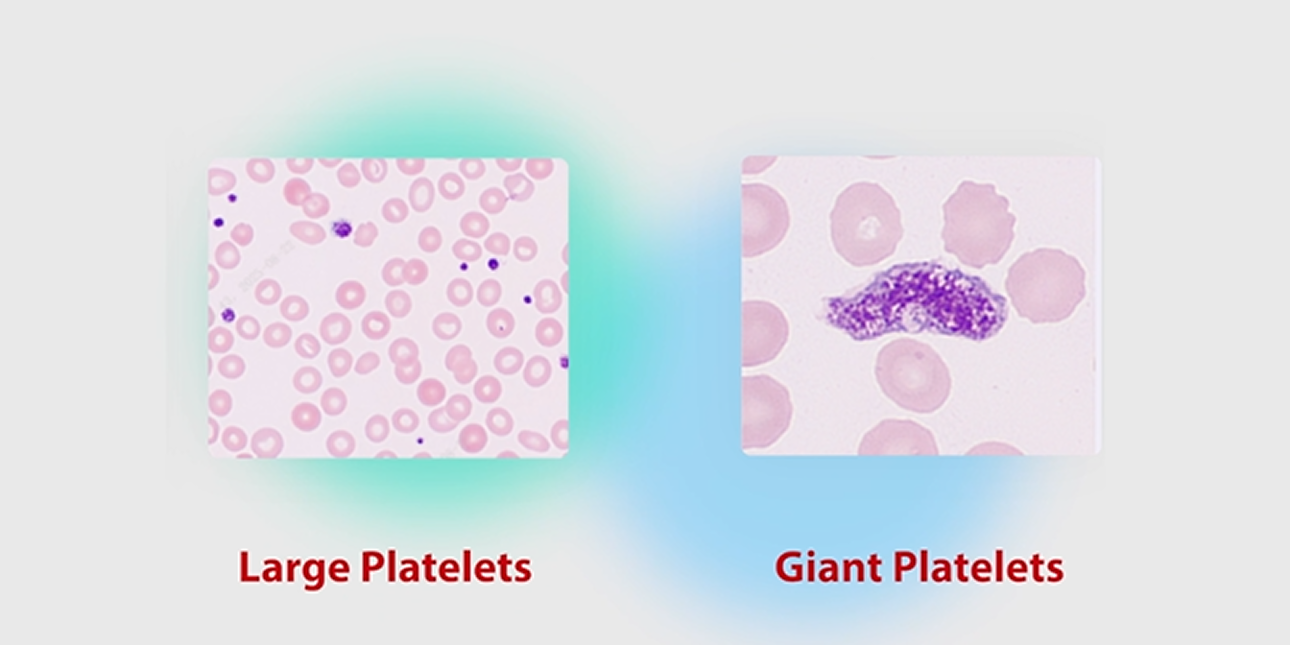

Dengue virus can directly or indirectly impair the human hematopoietic system. It particularly targets megakaryocytes in the bone marrow, which are responsible for platelet production, leading to thrombocytopoiesis suppression and consequently insufficient platelet production. Concurrently, the virus-induced immune response (such as immune clearance and disseminated intravascular coagulation) accelerates platelet consumption and destruction. This dual pathogenesis of decreased production and increased destruction results in a severe imbalance between platelet supply and demand, which is the central mechanism underlying the rapid decline in platelet count and elevated bleeding risk in dengue patients.

In clinical practice, both patients and healthcare providers face significant psychological stress. Patients endure the anxiety of an uncertain recovery timeline, while medical teams must contend with the unpredictable clinical course of the disease.

Dr. Sheela Devi notes: “Traditionally, dengue management involve drigorous monitoring of platelet count to check the severity of the disease. This approach often triggered panic and led to unnecessary platelet transfusions. lt not only drained the blood bank resources but also exposed the patients to transfusion-related complications. What we need is not only to understand 'what is happening' but also to predict 'what will happen.”

The IPF Breakthrough:

Predicting Recovery Before It Happens

A significant advancement in this regard is the clinical application of the Immature Platelet Fraction (IPF). IPF reflects the proportion of newly released, young platelets in peripheral blood, serving as a real-time indicator of bone marrow thrombopoietic activity. It can be measured simultaneously with a complete blood count (CBC) and differential (Diff) on automatic hematology analyzers, requiring no additional reagents or manual steps. This provides clinicians with a rapid, convenient, and standardized parameter to dynamically assess bone marrow recovery in dengue patients, supporting more informed clinical decision-making.

Dr. Ashvini Sengupta

Director of Lab Service, Manipal Hospital EM Bypass

IPF is a relatively recent hematological parameter used in monitoring thrombocytopenia, especially in severe dengue cases. A rise in IPF typically occurs 2 to 3 days before an increase in platelet count, indicating early bone marrow recovery. Therefore, IPF serves as a predictive marker for impending platelet regeneration.

A rising IPF serves as an early, direct indicator of recovering bone marrow thrombopoiesis. This rise typically precedes an increase in the platelet count by 2–3 days, providing clinicians with a critical predictive window. This early signal enables more informed clinical management. By anticipating platelet recovery, physicians can avoid unnecessary transfusions, optimize resource use, and better monitor a patient's hematopoietic response.

Case in Point: Dr. Ashvini Sengupta described a pediatric ICU case involving a child with severe thrombocytopenia. After a platelet transfusion yielded no improvement, trend analysis of IPF—interpreted alongside the static platelet count—supported the decision to withhold further transfusions. The child’s subsequent spontaneous platelet recovery validated this approach, preventing overtreatment and alleviating family distress.

Operational Advantages: The clinical utility of IPF is enhanced by its analytical practicality. As a parameter derived from routine CBC analysis, it requires no additional sample, reagents, or complex manual steps. This standardization makes it a viable and scalable tool even in resource-limited settings, supporting consistent application across different levels of healthcare.

A National Fight:

How India Is Turning the Tide Against Dengue

Over the past decade, India has significantly reduced its dengue mortality rate—from 0.2% to below 0.1%—through proactive mosquito control, adoption of new medical technologies, and strengthened public health campaigns and primary care capacity. Behind each statistic lies countless families spared from tragedy and brought renewed hope.

Dr. C.K.Mishra

Former Union Secretary, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India

Dengue control has two fronts: prevention, and diagnosis with treatment. Everyone has a role. People must keep their surroundings clean and free of standing water. Communities should act as watchdogs, raising awareness and monitoring risks. Governments must enforce laws strictly, provide adequate funding, and ensure hospitals are ready to care for those affected.

Whether in India or in communities around the world, and whether it concerns chikungunya or dengue, this is not merely an isolated local challenge, but a reflection of the global threat posed by vector-borne diseases. As noted by WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus: "Are we ready for the next pandemic?"

Today, technology is quietly providing an answer. More and more regions are now better equipped to respond to vector-borne diseases with greater efficiency and lower costs—and this, perhaps, is the most vital value of medical innovation: to empower healthcare technology in safeguarding every life, everywhere.