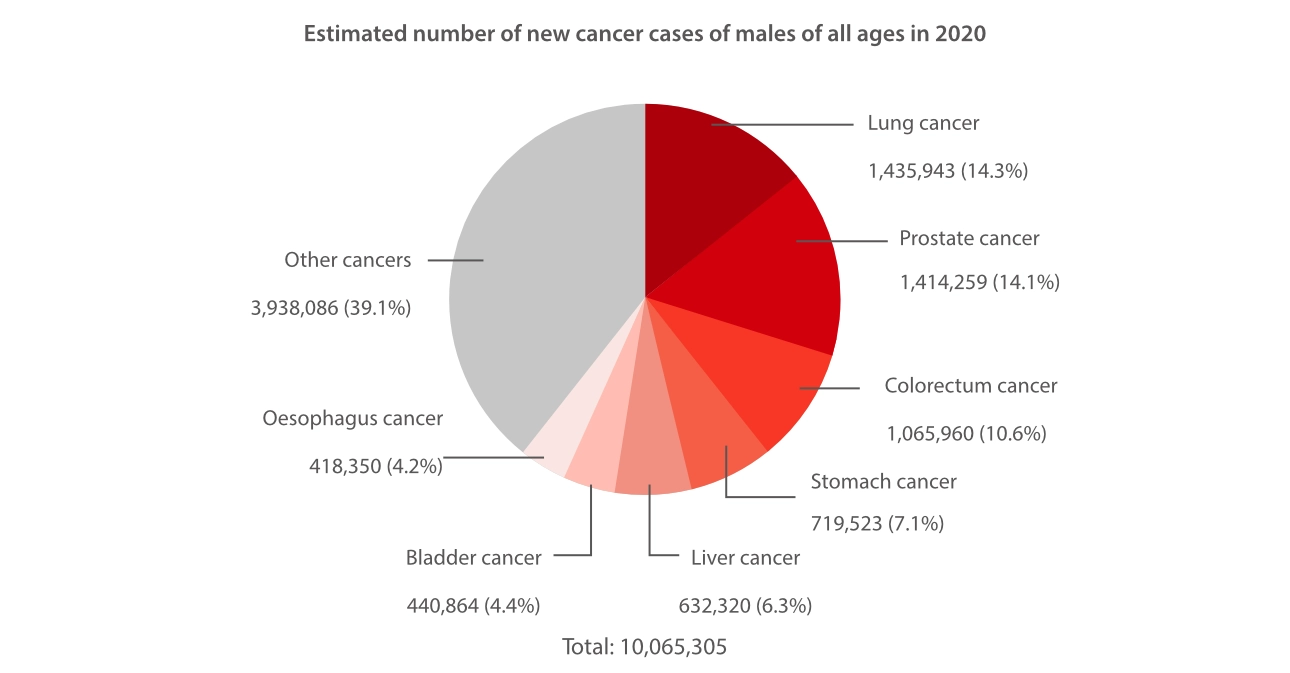

According to WHO data,[1] in 2019, the top three causes of death among men were cardiovascular diseases, malignant neoplasms, and infectious and parasitic diseases. Despite major advances in cancer research that have led to improvements in cancer treatment and declining mortality rates,[2] incidence rates for all types of cancer have remained stable.[3] As such, cancer continues to be a pressing public health concern that requires our ongoing attention.

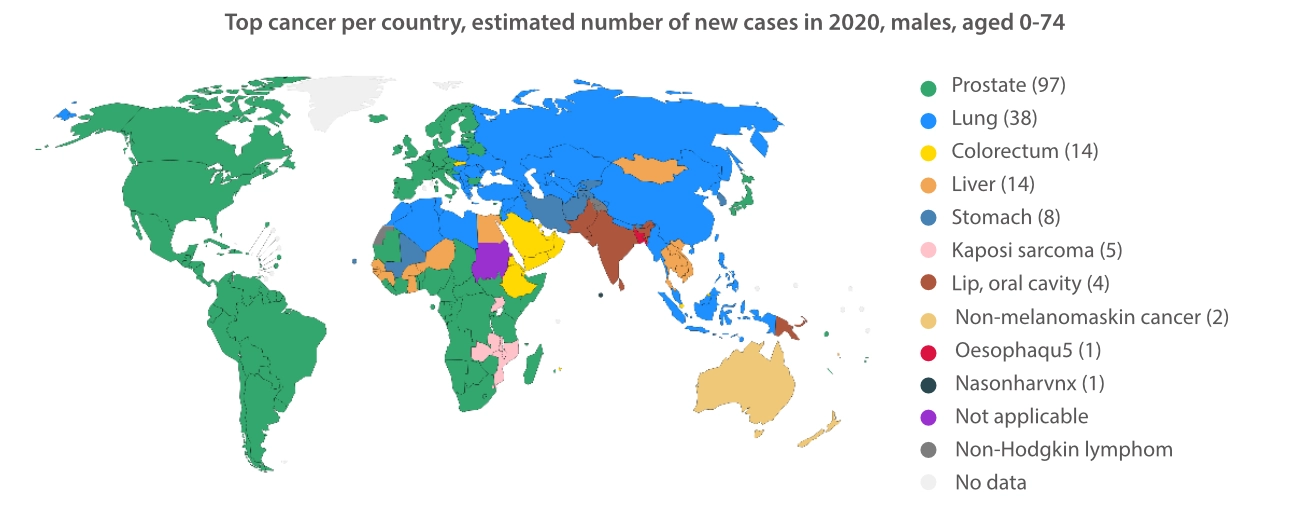

The most common types of cancer can vary between men and women. Breast, colorectum, and lung cancers are the top three most commonly diagnosed cancers among women. In contrast, lung, prostate, and colorectum cancers have exhibited the greatest increase in incidence rates among men.

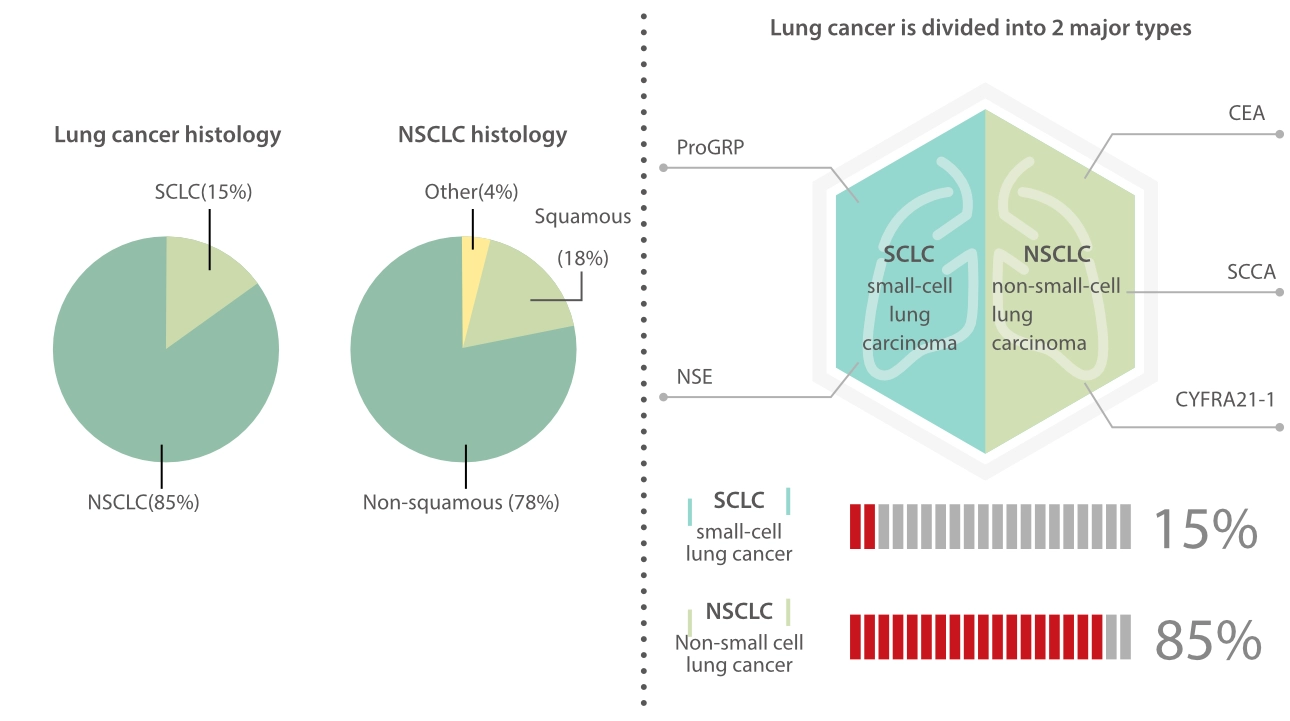

Lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among men in 2020, accounting for an estimated 1,100,000 deaths worldwide.[4] Generally, lung cancer can be categorized into two primary types: non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) and small cell lung cancers (SCLCs), accounting for roughly 85% and 15% of cases, respectively.[5] NSCLCs can be further classified into three main subtypes: adenocarcinoma, squamous-cell carcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma.The 5-year relative survival rates for NSCLC patients range from 9% to 65%, depending on the stage at which they are diagnosed.[6] SCLCs grow at a faster rate and are more challenging to treat than NSCLCs.[7] The 5-year survival rates for SCLC patients vary between 3.6% to 32.2% for women and between 2.2% to 24.5% for men.[8]

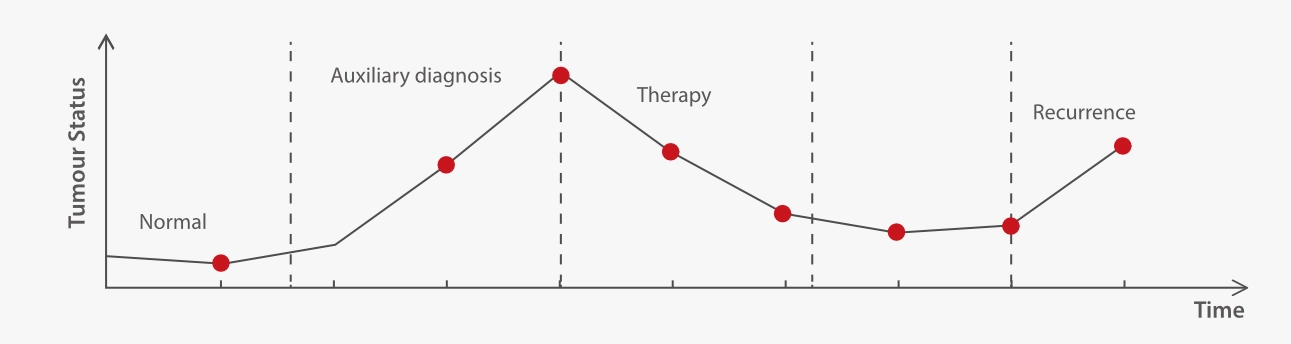

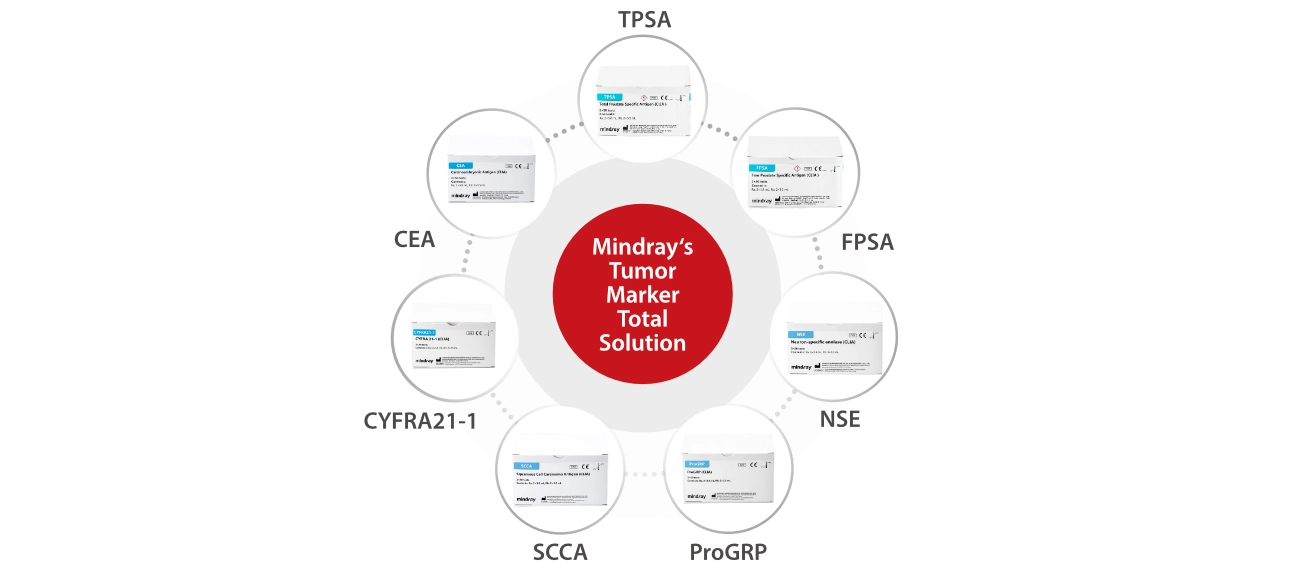

Typically, physicians would perform an imaging examination based on the patient’s medical history and confirm their diagnosis through biopsy results.[9] Besides conventional diagnostic techniques, serum tumor markers can aid in the diagnosis, prognosis, early diagnosis of recurrence, and therapy monitoring of cancer. Mindray’s comprehensive Lung Cancer Biomarkers, which are endorsed by the National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry (NACB) and the European Group on Tumor Markers (EGTM), can significantly support clinicians and patients in dealing with lung cancer. NSE and ProGRP are commonly used biomarkers for SCLCs, whereas SCCA, CYFRA 21-1, and CEA are often used for NSCLCs. Among these biomarkers, ProGRP is considered to be the most sensitive for detecting SCLCs.[10] Changes in ProGRP levels can serve as an indicator of treatment response and prognosis for SCLC patients.[11] Moreover, combining different lung cancer biomarkers can lead to improved sensitivity and accuracy, thereby enhancing their clinical significance.[12]

Prostate cancer is a common cancer that affects males worldwide, with a high incidence rate second only to lung cancer.[4] It ranked as the most prevalent cancer among males in 97 countries,[4] occurring more commonly in the developed world.[13] Prostate cancer tends to develop gradually and progress slowly, which is why most cases are diagnosed in middle-aged and older men.[14] In recent years, prostate cancer incidence has shown a slight uptick followed by a subsequent decline, whereas mortality rates associated with the disease have been decreasing slowly. An interesting observation is that the incidence of diagnosed prostate cancer is strongly correlated with the use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based screening in the USA.[15] The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against widespread PSA testing for men over 75 years in 2008 and for all men in 2012. As a result, there was a decline in the incidence of diagnosed prostate cancer, particularly early-stage cases.[16] However, there has been an increase in the number of unfavorable stage/grade prostate cancer cases.

Therefore, PSA testing for cancer screening should be used judiciously to detect the disease at an early and treatable stage, tailored to individual cases. PSA is produced by the epithelial cells of the prostate gland, and its level is typically low in the serum of healthy men.[18] However, an elevated PSA level is not only indicative of the presence of prostate cancer but also of other prostate disorders, including prostatitis and benign prostatic hyperplasia.[19] Therefore, there is no definitive PSA cutoff point that can conclusively determine the presence or absence of prostate cancer. Many physicians use a PSA cutoff point of 4 ng/mL or higher to determine if further testing is necessary, and PSA levels in the range of 4-10 ng/mL represent a ”grey zone” .[20] Currently, physicians may utilize other variations of PSA tests to better interpret the results, such as measuring the percentage of free PSA. Free PSA is a unique form of PSA that circulates freely in the blood without binding to proteins. Percent-free PSA (%fPSA) could be used to help to indicate the possibility of prostate cancer. Its level is generally lower in men with the disease than in healthy men. A biopsy may be necessary if %fPSA levels are abnormal.[19] In addition to screening, PSA levels are used for risk stratification, staging, and post-treatment monitoring.

As a leading provider of clinical diagnosis solutions, Mindray offers a comprehensive panel of tumor biomarker tests to aid in the diagnosis of various cancers. Leveraging our precise and efficient chemiluminescence platform, we are committed to promoting men’s health and well-being around the world.

References

[1] Global Health Estimates 2019: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2019. Geneva, World Health Organization; 2020.

[2] Source: IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2019)

[3] Source: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)

[4] Source: GLOBOCAN 2020

[5] Thai, A. A., Solomon, B. J., Sequist, L. V., Gainor, J. F., & Heist, R. S. (2021). Lung cancer. The Lancet, 398(10299), 535–554. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00312-3

[6] https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

[7] https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4375-lung-cancer

[8] The SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2015. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER), U.S. National Cancer Institute.

[9] Horn & Iams 2022, "Diagnosing Lung Cancer".

[10] Molina R, et al. Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP) in patients with benign and malignant diseases comparison with CEA, SCC, CYFRA21-1 and NSE in patients with lung cancer. Anticancer Res, 2005

[11] Sunaga et al. Oncology 1999, 57,143-148

[12] Xianfeng Lu, et al. Meta-analysis of serum tumor markers in lung cancer. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za zhi. 2010, 13: 1136-1140.

[13] Baade PD, Youlden DR, Krnjacki LJ. International epidemiology of prostate cancer: geographical distribution and secular trends. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009 Feb;53(2):171-84. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700511. PMID: 19101947.

[14] World Cancer Report. World Health Organization. 2020. ISBN 978-92-832-0447-3.

[15] Eapen RS, Herlemann A, Washington SL 3rd, Cooperberg MR (2017). Impact of the United States Preventive Services Task Force ‘D’ recommendation on prostate cancer screening and staging. Curr Opin Urol. 27(3):205–9.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0000000000000383PMID:28221220

[16] Jemal A, Fedewa SA, Ma J, Siegel R, Lin CC, Brawley O, et al. (2015). Prostate cancer incidence and PSA testing patterns in relation to USPSTF screening recommendations. JAMA. 314(19):2054–61. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.14905 PMID:26575061

[17] Catalona WJ, Richie JP, Ahmann FR, Hudson MA, Scardino PT, Flanigan RC, et al. (May 1994). "Comparison of digital rectal examination and serum prostate specific antigen in the early detection of prostate cancer: results of a multicenter clinical trial of 6,630 men". The Journal of Urology. 151 (5): 1283–1290. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347 (17)35233-3. PMID 7512659

[18] Velonas VM, Woo HH, dos Remedios CG, Assinder SJ (May 2013). "Current status of biomarkers for prostate cancer". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 14 (6): 11034–11060.

[19] https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostatecancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/tests.html